One Story World, but Two Story Spaces?

The research in transmedia narrative, which is just a small part of the larger field of transmediality, often falls prey to a kind of “essentializing” gesture. Transmedia narrative, that is the simultaneous materialization of a story (including a story world) in a wide range of different media, is then seen as a new, theoretically all-encompassing form of narrative that brings together the features and experiences of supposedly less complex or at least less efficient forms of storytelling.

There are at least two reasons to challenge such a vision of transmediality as “super”-narrative. First of all, there is of course the (relative or partial) resistance of media to smoothly materialize the form and content of the initially defined story and story world: not everything can be told in any medium, on the one hand, and the specific way of telling of each medium may affect the initial story and story world to the extent that the very unity of the transmedia narrative may be jeopardized. Very simple ideas, but which resist the possibly homogenizing effects of transmedia storytelling. Secondly, and this is a much stronger and more interesting claim, there is also the fact that new forms of storytelling (and there are good reasons to suppose that transmedia storytelling in the digital age is an example of such a novelty) does much more than expand on existing forms or combine them in innovative ways. What may happen instead, is that new forms of narrative enable or even oblige to dramatically revise our existing vision of certain narrative categories.

This is exactly the point made by Daniel Punday in a fascinating recent article: “Space across Narrative Media” (Narrative, January 2017, 98-112; accessible via Muse). To crudely summarize: Punday observes that digital games often present a double spatial structure, that of the “primary” space as experienced by the characters (and/or the players) and that of the “orienting” space which serves as a background and which helps the reader (who is her different from the character/player) to get a larger framing of the story. To give a simple example (which is mine, not Punday’s): the “primary” space of the search for Eldorado may be an environment that resembles some exotic jungle in which the characters and players are deeply immersed; the “orienting” space may be a map of the world containing for instance details on commercial sea routes, which do not directly interfere with the jungle story but which definitely frame the narrative experience for the reader. This basic distinction is then reinterpreted by Punday with reference to Bakhtin’s distinction between two approaches of the chronotype: the view from inside the chronotype (the “primary” space) and the view from outside (the “orienting” space).

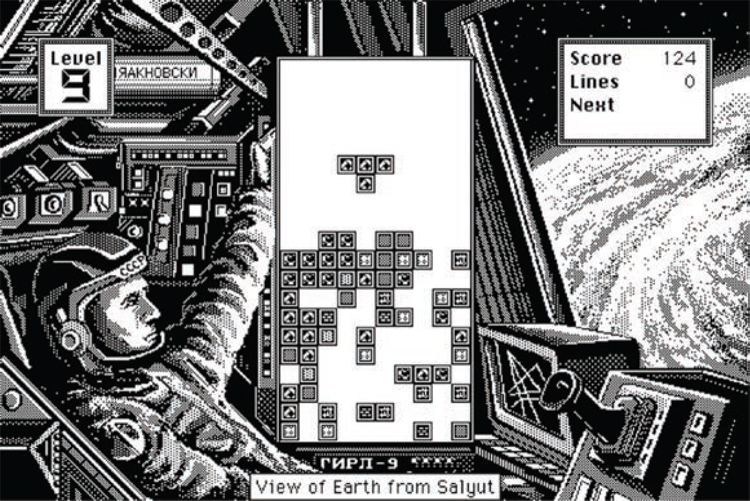

The next step in Punday’s argumentation is very logic. He notices that Bakthin’s distinction, which everybody “knew” without actually using is, is now become clear and ready for use thanks to a cliché of digital gaming, where space is generally presented this way. Punday gives the example of Tetris, where one finds a kind of baroque visual framing of the game itself (see image above).

This mechanism is not very different from Borges’s play with literary history in his text on “Kafka and His Precursors”, where he demonstrates that instead of being “prepared” by his precursors, Kafka actually “invents” them (that is: makes visible that before him there had been other writers doing something similar). At the same time, the return to Bakhtin is not a passive recovery of an understudied aspect of his theory: thanks to digital gaming, one realizes for instance that the combination of primary and orienting space is utterly artificial and that it does not (always) make sense to try to bring them together in one unified story space. The combination of both spaces is an artificial construction, but with major effects on the act of reading, which is generally reduced to the study of the primary space.

What has all this to do with transmedia storytelling? Basically this: transmedia storytelling is often seen as the “remediation”, that is the transformation of existing media in order to make them more powerful. But form the very moment that “remediation” is no longer seen in terms of linear transformation, the old being remediated by the new, but in more complex forms as an invitation to permanently revise our current knowledge of the past as well as the present and the future, it is of course no longer possible to define transmedia storytelling as a simple continuation or expansion of previous non-transmedia forms of storytelling. What transmedia storytelling should encourage us to do, is to use it as a tool to rethink the very notions of medium and narrative themselves.